No unified picture. Warring factions. I try to distill one, major model.

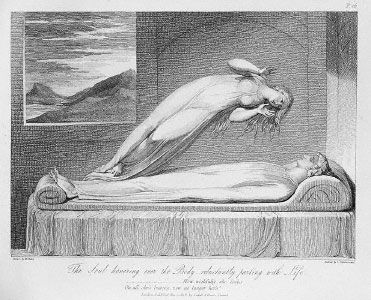

Soul that part in us we share with God. God’s spirit in us. It is given to us from God, is immortal, and returns to a trans-mundane existence after our death (“Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was: and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it” (Ecclesiastes 12:7)).

In this world it is human will, understanding, and unique personality. Most importantly: the soul is free. Free to decide to do the good or to do evil, free from subjection to the senses in its decisions. Being the main agent and medium of insight and control, it is through our souls that we conduct our lives, our soul acting as a governing agency in us (St. Paul, Augustine). Much of that governing is over the body, which, through the desires of the flesh opposes to the control of the soul. It is up to us to be strong and to take the side of the soul in leading a life in accordance with the commands of god.

Each human being has a unique soul, given to her or him in the process between conception and birth (the Catholic church teaches that the soul is present from the moment of conception on). It is our most precious good, and calls for moral protection of its being, as well as constant guidance.

From a transcendent point of view the soul is the agency that is responsible for the life we lead before God. Surviving our death, souls will be judged by God. If our life finds grace before God, the soul will gain eternal life in Heaven and enjoy eternal fellowship with God. If, on the other hand, the judgment is negative, the soul will be punished for the sins of our lives.

Buddhist beliefs

[Adapted from the article “Buddhism” in Encyclopedia Britannica.]

As individuals we exists in separation and limitation, which ground desires to overcome the obstacles, and desire is the basis of suffering.

Buddhism rejects the idea that the soul exists as a metaphysical substance, but recognizes the existence of the self as the subject of action in a practical and moral sense. Life is a stream of becoming, a series of manifestations and extinctions, without an underlying coherent agency. The concept of the individual ego is a delusion; the objects with which people identify themselves—fortune, social position, family, body, and even mind—are not their true selves. There is nothing permanent.

We can overcome the delusion of the mundane self and attain no self (an atman). But that means that we deal with the appearance of the self or soul. What we take to be our self consists of five aggregates or constituents (khan has): (1) corporeality or physical forms, (2) feelings or sensations, (3) ideations, (4) mental formations or dispositions, and (5) consciousness. Human existence is only a composite of the five aggregates, none of which is the self or soul. A person is in a process of continuous change, and there is no fixed underlying entity.

Concerning the soul, two elements of the complex and diverse Buddhist tradition are important. On the one hand, we can overcome the delusion of self by attaining states of non-selfness. Yoga practices are a means towards this end. Not only can we exist in a state of non-self. We are also more enlightened beings in that state, closer to our true selves than when we move in the world of desire and identification with mundane values. On the other hand, depending on how we live, we are reborn in different incarnations in other lives. This is of course difficult to conceive without assumption about something permanent that ‘underlies’ different existences.

The two religious attitudes – with their very different models of the soul, show quite neatly how basic notions depend on basic values of world-views: the Christian world-view modeling of the soul manifests the idea of a creator God to whom we are responsible in our lives and beyond. It also lets itself be dominated by the idea of a conflict in value between body and soul. The soul knows and pursues the good, the body is dominated by desires and appetites that fall on the bad side, and the idea that the soul ought to rule a recalcitrant and basically immoral body.

The Buddhist notion, on the other hand, conceives of our mundane existence in a negative way. It is thus let to see a problem in what is commonly called ‘soul.’ In setting up a practice of overcoming the negative, the soul is put into the role of that which is to be overcome, and the overcoming as the shedding of an illusion.

The soul today?

Sciences – Psychology: It is the psyche of psychology and social sciences, the neural network and system for neurology, and the mind for philosophy, and for each of these it is many different things, in many different perspectives. No unified picture. A scientific view tries to explore psychic functions scientifically, either reducing them to behavior, or conceiving of them as activity of our brain and our nervous system. Psychoanalysis has a model, according to which the psyche is the interplay of mostly hidden agencies – ego, superego and id – best interpreted as conferring meanings, overt and hidden to our everyday comportment. The discipline of psychology divides into explorations of development, motivation, cognition, social, and others. In addition methodological orientations differ widely. We find quantitative methods, qualitative analysis, interpretation of meanings. Some of the disciplinary branches are simultaneously practical – e.g. ‘clinical psychology’ - giving rise to various forms of counseling and therapy. The philosophical branch is not more coherent. A mess, if one thinks there ought to be a more coherent and more comprehensive notion. And us? Barely anyone thinks in terms of ‘soul.’ Modern use seems to be confined to religious contexts and popular music. ‘Mind’ and ‘mental’ have become the collecting terms for our desires, feelings, thoughts, memories, imaginations, decisions and volitions. We operate with these concepts day in day out, but without understanding what we are saying when we say ‘this is what I want’ or ‘I am angry.’

Aristotle’s soul

The soul is a well-circumscribed part of our whole being. Starting with our own soul: We essentially are rational animals. Now each specimen of a human being is a unit of soul and body: “soul and body make up an animal.” (423a2). Plants are also included into the domain of substances that unite soul and body. As bodies are also found in the world that is not alive, soul must be the distinctive feature of life. But what are ‘body’ and ‘soul’ doing inside of the living unit, each of them present in that unit, how are they united and what is each of them there?

Our first idea will be: there is a body, describable in biological term: the thing that lives. And this body is inhabited by a soul that does what we ascribe to the psyche: it perceives, feels, remembers, dreams, thinks, desires, wills. We will, perhaps, also ascribe structural traits to that soul, things like character traits. These are NOT Aristotle’s ideas.

The Hylomorphic Conception

Soul as from, body as matter:

Body and soul are, in relation to each other, matter and form of the human being. This is called Aristotle’s hylomorphic conception of man. Body is matter=hyle; soul is form=morphe.

A first comparison:

soul : body ~ Aristotle-shape : bronze

The analogy is from the point of view of form and matter: Just as Aristotle-shape is form relative to bronze as its matter in the statue, so soul is form relative to the body as its matter in the living being.

We aren’t artifacts. Not yet, perhaps soon. That means that we need to

look for elements that can count as form relatively to the body. Now Aristotle’s

decisive move: He lets himself be guided by the idea that life is the shared

essential trait of all living beings, and that life is their shared form. ‘To

be alive,’ ‘to be a life’ is our most basic function, together

with the world of plants and non-rational animals. (Note the process-indicating

prefix “a-“ in “alive!). Aristotle’s idea and thesis:

The soul is, or better includes, the system of life-constituting functions for

the specific being. Things of soul-character, functioning as form, confer life

to living beings. If all soul elements are absent, we do not have life. And

all and only those elements that contribute in a forming manner to the conduct

of life of a specific form of life count as soul- elements. We see right away,

that this excludes the idea that the biological body can be a living body without

a soul. According to Aristotle, no live body is without soul. You will quickly

understand that this is not the venerable animism that attributes to each living

being an individual complete soul, assuming that the tree feels, perceives,

acts intentionally, communicates with us, a soul that suffers when the tree

is hit and says ‘no’ when the wind gets into its crown and shakes

it. This is the attitude of the fairy tale, of certain religions wrongly called

primitive, and of our own ancestors. Aristotle thinks differently. More precisely:

he thinks the issue, instead of basing his attitudes on faith.

His idea of how body and soul are integrated in the living being is expressed in highly intransparent formulae: “The soul must be substance qua form of a natural body which has life potentially.” (412a18) and “The soul will be the actuality of a body of this kind,”i.e.of a “natural body which has life potentially.” And “the soul is the first actuality of a natural body which has life potentially.” What is Aristotle saying here? Taken in abstraction from all soul elements the body of a living being is not alive. It lacks the necessary form ‘life.’ But, being able to be alive if formed by a soul, that body must be apt to receive that form, just as the bronze and the marble must be apt to receive the form of the statue. This is why body, taken in isolation, has life “only potentially.” On the other hand, when the life-conferring soul comes to ‘ensoul’ that body, it is also ‘enlivening’ it. (Note the prefix “en-“ in ensouling” and “enlivening.” It presents the following verb as saying that there is an activity that brings about a result.) As these activities are of the kind of a process and an activity, they are ‘actuality.’ The soul is therefore the actuality of a living body. ‘Actuality’ says two things: on the one hand, the soul is a condition for life; on the other hand, being alive is an activity first, and a state only second. The form-matter distinction is thus a first factor that lets the Aristotelian soul be distinct from what mind-functions are for us. For Aristotle, life=Bios is a soul-activity!

What, then, is the body in abstraction – and what does the soul do when it enlivens its body? The body in abstraction is close to the item that lies before us right after death, or better, in cardiac arrest: all the organs are there, everything that allows life-processes to unfold is in place. But the processes do not take place. These processes may resume, and if they do, the Aristotelian life-conferring soul returns to its matter. (Play this through for different stages of human gestation from conception to birth. Is there a likely stage or development for the life-conferring soul to be in place? Where would that be?).

Can body and mind exist separately?

The fact that soul is enlivening from to the potentially living body has an immediate consequence. Philosophy has been plagued by the question whether body and soul can exist independently from each other. You have heard that the Christian religious idea asserts independence of the two. And you will hear soon from Ann that Descartes thinks so too. This idea is called body-mind, body-soul dualism. Its opponents claim that body and mind cannot have independent existence, and often achieve this by claiming that there is only one kind of item: either everything is material – both body and mind, or everything is mind, bodies and matter as well as soul. These are two monist positions. Now Aristotle sends them back to back: “It is not necessary to ask whether soul and body are one, just as it is not necessary to ask whether the wax and its shape are one, nor generally whether the matter of each thing and that of which it is the matter are one. For even if one and being are spoken of in several ways, what is properly so spoken of is the actuality” (412b6-9).

No after-life for the soul after loss of the body it enlivens. All that can be said about the soul after death is that it is a potentiality for ensouling. And, as the uniqueness of the individual substance and the remembered trajectory of a life contribute decisively to the individuality of the soul in a living being, that individuality depends on the body. In other words: No continuation of individual soul, not even in the form of a lifeless shadow (Greek mythology), a soul that can be reincarnated (Buddhism) or a soul that can be subject to punishment or bliss in an after-life (Christianity).

Soul-body interactions.

Interactions: Behavior occurring between two agents or agencies in such a way that the action of one directed at the other is connected with the action of the other at the direction of the first: action1 (x ? y) connected with action2 (y ? x)

The basic form of interaction has already been discussed: the soul confers life to the body, which, in isolation is alive only potentially; the body offers the potential for actualization to the soul, which does not have reality without being embodied. The two are interdependent. When one occurs, the other also occurs. But we still have, as it were, two agencies, and therefore something a change that can be analyzed from the perspective of the one or the other.

But we also need to look into others, based on the fact that soul is differentiated into different subfunctions, and needs to perform its life-conferring enabling function at different places in the differentiated organism. “If,” says Aristotle in a passage not printed in our reader, “ the total soul integrates the whole body, then it will be the task of every part to integrate a part of the body.”

The main subfunctions that interest us here, are:

the nutritive and reproductive soul-function

affections and feelings

perception and memory

the intellect

This time only the most basic of them:

The nutritive and reproductive soul-function is the “first and most commonly possessed potentiality of the soul, in virtue of which they all live.” (415a25) The passage makes clear that these belong to all living things. Aristotle thinks that there is something in the plant, a faculty, that is active, and makes it go after nutrition and makes it produce whatever is the reproductive mode of the plant. (This corresponds to my third feature of formative function: force that forms, formative form.) We, of course, analyze the system of roots and of the organization of the tree towards reproduction of another in such a way that we find these functions in structure and chemistry. For Aristotle, they are soul. In other words: those who study life-functions of plants would be plant psychologists in Aristotle’s eyes. Once again: nothing obliges Aristotle to think of the soul as a spiritual element, different from material elements. His thinking is different from ours, tinted by 2000 years of Platonism and Christianity. But he thinks of an interaction here, between two agencies that play different roles in that interaction. We do not think like that. How can one think like Aristotle? First, he does not possess the chemical knowledge we have. Philosophically more interesting is the question: How can he even distinguish forming activity from formed form? If, as he says, the body is prepared to receive the form of life – the body is life potentially – how can one even distinguish the forming force and the formed recipient? Our chemical analysis does not do this. Indeed, it does not even have a model that calls for that thought. It looks as if only a conception that distinguishes soul and body as mental and corporeal, and let the metal be like the sculptor to the corporal that is like clay doe his distinction make sense. Nature as clay animation!?

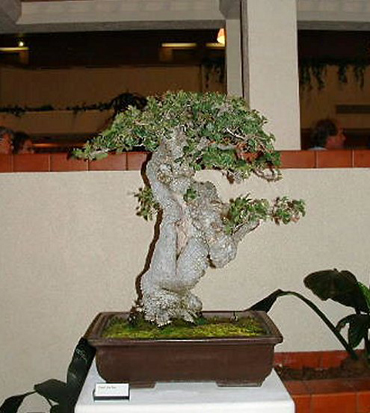

[From: Finding a Soul in Bonsai. http://www.artofbonsai.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=961

Part of the caption: “The Japanese have a word known as Kami. As far as I know I am about the only person who has chosen to associate this word with Bonsai. Other Bonsaists choose to use Wabi and Sabi when defining the quasi-spiritual aspects of bonsai. Kami is for lack of a better definition defined as spirit or soul, an almost personality that inhabits things of great beauty, power, and artistry. It is a force that almost gives a thing a life of its own that supersedes a tree or a pot or a sword, or a landscape.”

On scrutiny the distinction between an active, forming function in our plant

and a passive, formed function makes sense if we make one important assumption:

the body that is enlivened by the nutritive and self-maintaining soul of the

plant is not just lying there, waiting to be ensouled, perhaps longing for it

like Snow White for the kiss of her Prince. The body is also recalcitrant. It

has its own resistance to being kept alive. The form has to constantly overcome

that resistance in maintaining that body alive. Taken separately, the body is

not just propensity to be ensouled, made and kept alive. It is also an item

in its own right – potentially – and that resistance needs constantly

to be overcome. We see it at work in illnesses, aging, in the deviations that

can occur in generation. The idea of soul as enlivening form and body as formed

life is therefore an idea that combines the idea of fit – the propensity

of each to unite with the other to constitute a specific form of life and the

idea that there is an opposing tendency in life – something that opposes

being in that form. Only together do they account for life: Not ‘nature

as clay animation,’ but: nature as antagonism of forces. Nature is the

world of change. Its living domain changes as a consequence of internal antagonism.

A comparison of soul features in:

| - - - - - - - Aristotle - - - - - - - - - |

- - - - - - - Modern - - - - - - - |

| Hylomorphism: body and soul distinct but in interdependent relation. Neither dualism (Descartes) nor monism (materialisms) |

Dualisms: body and soul each have their own being; may have independent destinies. Monisms: materialism denies independent being to soul/mind |

| Soul enlivens body; body gives reality and sustains soul in existence (gives ‘actuality’ to soul) |

Biological life is mind-independent; mind-functions are ‘add-ons’ to life. |

| Hierarchy of basic faculties: |

Multitude and plurality of functions; related, but without systematic order, only partially ordered. |

| Soul-functions are active, enabling sources of performances, corporeal functions are soul-activated; affective and perceptive soul-functions show double aspect: soul appearance and corporeal appearance. Example: sight is due to the eye-soul making the eye perform its purpose, but depends on the eye being hit by object, and recording the object. Hylomorphist: sight is interaction of eye-matter and sight-form. |

Mind-functions are dependent on body-functions;

Reductionist: sight is but a complex of neurological events. |