Forum!

This Friday, 11 a.m., in this auditorium.

Come

to ask your questions!

Soul

2: The Faculties of the Soul:

Summary

Soul is form to body as matter in living beings. Soul an essential form: What is it to be a living being? To be ensouled. What is it to be a living being of the human kind? To have a rational soul. (There’s more essence than that). Most important function: Soul the life-conferring element in the compound ‘living being.’

A complex, unified, dynamic forming element that not only confers life, but also determines the specific form of life in its distinctive features. At the same time: something that is fashioned by life, and changes over time.

Aristotle neither a dualist concerning body and soul, nor a monist reducing one of the elements by saying that both are just matter/stuff or are just spirit/mind. Hylomorphism is different from both dualism and reductive monism.

Most important faculties (expanded

from last time):

the faculties that regulate growth,

nutrition and reproduction

the faculty of locomotion

the faculty for affections,

feelings, and desires

he faculties for perception and

memory

the faculty of intellect and

practical reason

Hierarchy

Faculties in a hierarchy: the

‘lower’ faculties presupposed for the ‘higher’ ones. As there are living beings

that possess only some of them, the faculties organize an order of realms of

living beings:

‘Vegetative soul:’ Plants have only

the faculties of growth, nutrition and reproduction.

‘Animal soul:’ Animals have the

faculties that regulate growth, nutrition and

reproduction,

locomotion, affections, feelings, and desires, perception.

‘Human soul: Humans possess the

faculties that regulate growth, nutrition and

reproduction,

locomotion, affections, feelings, and desires, perception,

intellect,

and practical reason.

Not: the lower beings have only . .

., and the higher beings add . . .. The integration into the unified soul is

different at each level. The vegetative faculty functions differently in humans

(hunger, thirst) when compared to plants, but it still is vegetative, because

it fulfills the same purpose.

In detail, just the barest outlines:

The nutritive and reproductive

soul-function:

It is the “first and most commonly

possessed potentiality of the soul, in virtue of which they all live.” (415a25)

The passage makes clear that these belong to all living things. Aristotle

thinks that there is something in the plant, a faculty, that is active, and

makes it go after nutrition and makes it produce whatever is the reproductive

mode of the plant. (This corresponds to my third feature of formative function:

force that forms, formative form.) We, of course, analyze the system of roots

and of the organization of the tree towards reproduction of another in such a

way that we find these functions in structure and chemistry. For Aristotle,

they are soul. In other words: those who study life-functions of plants would

be plant psychologists in Aristotle’s eyes.

Nothing obliges Aristotle to think

of the soul as a spiritual element, different from material elements. His

thinking is different from ours, tinted by 2000 years of Platonism and

Christianity. But he thinks of an interaction here, between two agencies that

play different roles in that interaction. We do not think like that. How can one

think like Aristotle? First, he does not possess the chemical knowledge we

have. Philosophically more interesting is the question: How can he even

distinguish forming activity from formed form? If, as he says, the body is

prepared to receive the form of life – the body is life potentially – how can

one even distinguish the forming force and the formed recipient? Our chemical

analysis does not do this. Indeed, it does not even have a model that calls for

that thought. Our genetic perspective does exactly that, but only for growth

and renewal of cells. Alas, also for the degeneration of aging. It looks as if

only a conception that distinguishes soul and body as mental and corporeal, and

let the metal be like the sculptor to the corporal that is like clay does his

distinction make sense. Nature as clay animation!? NOT Aristotle’s conception.

To be form and formative does not imply being mental in the sense of

‘mind-stuff.’

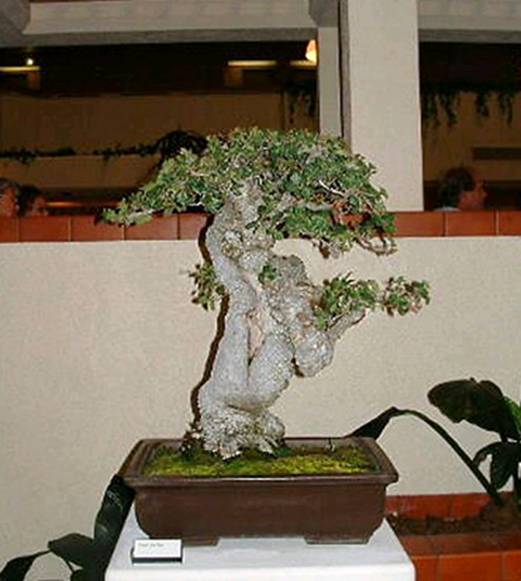

[From: Finding a Soul in Bonsai. http://www.artofbonsai.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=961

Part of the caption: “The

Japanese have a word known as Kami. As far as I know I am about the only

person who has chosen to associate this word with Bonsai. Other Bonsaists

choose to use Wabi and Sabi when defining the quasi-spiritual

aspects of bonsai. Kami is for lack of a better definition defined as spirit or

soul, an almost personality that inhabits things of great beauty, power, and

artistry. It is a force that almost gives a thing a life of its own that

supersedes a tree or a pot or a sword, or a landscape.”

Propensity and antagonism:

On scrutiny the distinction between

an active, forming function in our plant and a passive, formed function makes

sense if we make one important assumption: the body that is enlivened by the

nutritive and self-maintaining soul of the plant is not just lying there,

waiting to be ensouled, perhaps longing for it like Snow White for the kiss of

her Prince. The body is also recalcitrant. It has its own resistance to being

kept alive. The form has to constantly overcome that resistance in maintaining

that body alive. Taken separately, the body is not just propensity to be

ensouled, made and kept alive. It is also an item in its own right –

potentially – and that resistance needs constantly to be overcome. We see it at

work in illnesses, aging, in the deviations that can occur in generation. The

idea of soul as enlivening form and body as formed life is therefore an idea

that combines the idea of fit – the propensity of each to unite with the other

to constitute a specific form of life and the idea that there is an

opposing tendency in life – something that opposes being in that form. Only

together do they account for life: Not ‘nature as clay animation,’ but: nature

as antagonism of forces. Nature is the world of change. Its living domain

changes as a consequence of internal antagonism.

Affects

Focusing on us: together with perception our animal part, both of course integrated into the human soul. Affects and their correlate event, affections, are our good old friend pathos. They are experiences

(a) related to the impact of some state of affairs or occurrence – being insulted, meeting a person, being confronted with a dangerous situation

(b) consist in a feeling response to the impact of the state of affairs or event – anger about insult, love for that person, fear in front of danger.

(c) a motivational force or power – wanting to take revenge, desiring the beloved person, dealing with fear through flight, confrontation or danger-removing response.

A triad of conditions: impact from the outside of the soul, soul-response to impact, and action or behavior that enacts or acts upon the affect. Main problem: How do we deal with the ‘emotional’ pressure of affects towards direct translation into behavior (thought to be the animal response).

Perception

In perception we obtain knowledge of things that affect our sensuous organs: touch, vision, the auditory, taste. To perceive is to be aware of differences – between substances, between their qualitative characters, between relation between them. For animals this occurs without the help of concepts. Perceptions are our primary link with the world around us. Being cognitive, they are not directly linked to responsive behavior. Responses to perceptions will come about in the chain ‘perception-affect/desire-practical reason-action.’

In passing two oddities of Aristotle’s idea of perception. All perception relies on an organ of perception. This makes our whole body surface and much of our inside functioning as the organ of perception to touch. The organ is kept in function by specific formative elements. The eye (physiological) is in seeing condition because a seeing faculty is active in it. The other: perception can’t be wrong. We do not think that way. But Aristole has the idea that the form of the thing affects us and communicates its form to our sense organ. And in this process, nothing can go wrong. When we are in error, we merely misinterpret the form we receive.

Desire

Our selection deals mainly with affects. But it mentions desires (414a32). For those who want to read beyond the assigned texts: De Anima, Chapters 9 & 10.

I desire that beautiful peach I see at the Farmers Market. That means: I want to have it, perhaps to eat it. But it’s out there, still belonging to the vendor. Desire is normally understood as lack: we can only desire, what we do not have in the way that would satisfy our desire. We feel this lack, and an urge to satisfy the desire. Satisfaction, we think, fulfills that desire, the lack disappears, and with it that specific desire.

Aristotle thinks about desire with a twist: desire is what makes animals, us among them, go after things. Why did I reach for that peach? Because I desired to eat it. (That’s an explanation) But also: There is a peach in front of me. I desire that peach. So I have a reason to reach for it. Animals pursue of objects of their desire by changing place: hunting, collecting, planting and harvesting, etc. Desire – a way of being affected, but already filtered by rational factors – occurs only in forms that can move and that will move in the pursuits of objects that their life-form is after. Desire are the thing that sets in motion goal-directed behavior in living beings of the animal kind, human as well as non-human.

Desire shares with affects like anger and fear an urge to behavior that pushes towards immediate satisfaction, regardless of obstacles and reservations. But in humans it participates in the general malleability of the vegetative and animal drives in us.

Intellect

The intellect is “the part of the soul by which it knows and understands” (De Anima iii 4, 429a9-10; cf. iii 3, 428a5; iii 9, 432b26; iii 12, 434b3). Having the intellectual faculty or faculties is essential to being a human. The human rational faculties do not just understand things; they are also active in planning and deliberating, i.e. in the course of action. Aristotle thus distinguishes in the rational the "practical mind" (or "practical intellect" or "practical reason") from "theoretical mind" (or "theoretical intellect" or "theoretical reason").

What is the intellectual activity? We think in terms of concepts, and we put together concepts when we make judgments in which we assert something as being so, or conclude that something is to be done. When we do this, we use forms. The intellect is also the power of forms. Life, animal, plant, pathos and logos, matter and form, soul and body – each of them a form we use in intellectual activity.

Now in using these forms when thinking is being performed, these forms must be available to us, or come to be available to us.

Where are the tools and media of the intellect when they are not processed in thinking? Do they come from somewhere – ‘out of . . .’ – when they come up in thinking? The most proximate idea would be that the intellect has the forms of thinking in form for a potential for thinking, something that gets actualized in thinking activity. The parallel with the relation of body and soul would suggest this idea. But Aristotle says: The intellect is nothing before it is thinking. Saying this he seems to be denying a differentiated intellect under conditions of a silence in thinking. The intellect would then be a pure blank faculty, a slate, in which the thinking occurs as writing occurs on a blank slate.

We do not just manipulate forms when we think and contemplate. We claim knowledge, validity of our arguments, and correctness of our practical reflections. Most of these things do not just go on as independent performances of the intellect, but must be thought to be true or correct. For Aristotle that means that the forms through which we think are also the forms which inform the reality of the things that are the objects of our thought. The forms of our thinking and the forms of reality coincide. And it is when the forms through which we think correspond to the forms of things that are, and then, and only then do we have truth and correctness.

How does that correspondence happen? It happens through the fact that the thought peach we subject to a formal analysis asking: what is it to be a peach (we are not looking at it; the operation is an operation of the intellect) represents the form of the peach, and not just of this specific peach, but of all possible peaches ‘out there.’ Representation of forms through forms, and structural similarity, also called isomorphism, are the characteristics of thinking.

This would also hold of the contemplative forms ‘form,’ ‘matter’ and others. When we use these in thinking they turn out to be the forms of our thinking and, simultaneously, comprehensive features of the world.

A dynamic relation between different faculties

I have said that the different faculties integrated with each other. Also pointed to the fact that they are both capable of cooperation and of antagonism. Cooperation occurs, for example, when perception presents to us an object of desire or a form that is to be contemplated. Antagonism occurs when we desire something very strongly, but reason tells us that we ought not to go after it. Now we tend to think of that struggle as a conflict between two sides, where either the one or the other wins: we are too weak to control our desire and suffer the consequences; we are strong enough to control, and prevent the desire from guiding us towards the final activity of trying to satisfy the desire. Christian doctrine with its dualism of body and soul, and its ‘either-or’ of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ is a major factor for that belief.

I am turning to Sappho to show you a different and more subtle way of dealing with the antagonism. Here are four of her poems, in all likelihood fragments of longer poems. But, I think, each of them also expressing thought, and counting as thinking. This thinking is a specific type of activity called contemplation. I would like to call it ‘poetic contemplation,’ even if it is not confined to poetry.

I

Love shook my heart

like the wind on the mountain

rushing over the oak trees.

II

The moon has set,

and the Pleiades as well;

in the deep middle of the night

the time is passing,

and I lie alone.

III

Desire shakes me once again:

here is that melting of my limbs.

It is a creeping thing, and bittersweet.

I can do nothing to resist.

IV

Sappho, when some fool

Explodes in rage

in your breast

hold back that

yupping tongue!

Mastery, or slavery, or, perhaps, neither?

A comparison of soul features

|

- - - - - - - - Aristotle - - - - - - - - - - - |

- - - - - - - Modern - - - - - - - - - - - |

|

|

|

|

Hylomorphism: body and soul distinct but in interdependent relation. Neither dualism (Descartes) nor monism (materialisms) |

Dualisms: body and soul each have their own being; may have independent destinies. Monisms: materialism denies independent being to soul/mind |

|

|

|

|

Soul enlivens body; body gives reality and sustains soul in existence (gives ‘actuality’ to soul) |

Biological life is mind-independent; mind-functions are ‘add-ons’ to life. |

|

|

|

|

Hierarchy of basic faculties:

|

Multitude and plurality of functions; related, but without systematic order, only partially ordered. |

|

|

|

|

Soul-functions are active, enabling sources of performances, corporeal functions are soul-activated; affective and perceptive soul-functions show double aspect: soul appearance and corporeal appearance. Example: sight is due to the eye-soul making the eye perform its purpose, but depends on the eye being hit by object, and recording the object. Hylomorphist: sight is interaction of eye-matter and sight-form. |

Mind-functions are dependent on body-functions;

Example: sight either coincides with or is due to neurological processes in the eye, the nerves and the brain. Reductionist: sight is but a complex of neurological events. |