HCC Winter 2008

Week 2b: Renaissance Art, Lecture 1: Alberti and the Rhetoric of Painting

I. Wrapping Up Shakespeare: Pyramus and Thisbe

The play that the mechanicals are putting

on: Pyramus and Thisbe

> from the Latin poet Ovid

> source text for Romeo

and Juliet

> the Mechanicals’ staging worries:

::frightening

the ladies

:: how to represent Wall and

Moonshine

Wall: played by Tom Snout the Tinker

Chink: ditto (with his finger and thumb!)

Moonshine: played by Robin Starveling the Tailor

with a lantern

Where’s the humor?

> They could have made props!

> They misjudge the audience’s

imaginative and rational capacities.

The challenge for directors:

> Keep it funny.

> Don’t make all the jokes at the

expense of the Rude Mechanicals.

> Bring it back to the main plot.

What WALLS have

separated our lovers?

= the law of the

father that disallows the woman’s consent, young people’s self-determination

What CHINKS have they discovered?

elopement into

the forest;

holidays as social scripts for experimentation with

courtship

holidays as religious scripts for explorations of

“mystery”

And where’s the MOONSHINE?

Moonshine is the

magic of theatrical art – not just special effects, but our willingness to

enter into the fictional world presented to us. Moonshine is created through the

“constancy” of the performers collaboratively “bodying forth” the imagination

of the poet; and through the “constancy” of the audience willing to witness

“all together” the stories that they see and attribute coherence and meaning to

them.)

II.

Alberti and the Rhetoric of Renaissance Painting

Leon

Battista Alberti, 1404-1472

Alberti was an amateur painter, but not a

professional. Instead, he studied law and classical rhetoric and participated

in the movement of Renaissance humanism, which looked to the classical

tradition of ancient poetry and oratory in order to develop new forms of

secular (non-religious) literature, including political speeches, philosophical

dialogues, and love poetry. Alberti wrote humanist treatises and dialogues on

painting, architecture, the family, law, and cryptography.

My

Thesis: Alberti’s

Rhetoric of Painting

In his treatise Of Painting, Alberti uses classical rhetoric in order to link the

craft of painting to the intellectual work of orators and poets like himself.

Alberti also uses rhetorical theory in order to explain how paintings

communicate their messages to a broad audience of viewers.

(On the audience of paintings, see pp.

66-67.)In his treatise Of Painting,

Alberti transfers ideas from classical rhetoric into the art of painting. His

goal is to present the artist as an intellectual worker rather than a manual

one. Alberti also uses rhetorical theory in order to understand how paintings

communicate their messages to a broad

audience of uneducated as well as educated viewers.

The

Middle Ages: Painting is a handicraft, part of the

guild system.

The

Renaissance: move to transfer the arts from the craft

system to the liberal arts.

The

liberal arts: Grammar, Rhetoric, Dialectic, Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy, and Music.

Alberti emphasized the connection between

painting and geometry in Book I, and between painting and rhetoric in Book II.

Notice that literature is not listed as one of the traditional liberal arts. In

the Renaissance, what we call literature -- poetry, novels, plays -- was still part

of rhetoric.

Compare

Alberti and Shakespeare: Recall Shakespeare’s bid to identify

theatrical making with higher forms of intellectual work in A

Midsummer Night’s Dream, by distinguishing his play from the craft

tradition represented by the Rude Mechanicals. (Difference between Alberti and

Shakespeare? Shakespeare also acknowledged continuities between theatrical

making and the traditional crafts. Alberti definitely downplays these links. He

does, however, see painting as addressing both educated and less educated

audiences. See Of Painting, p.

66-67.)

Dates and organization of the book:

1435: De Pictura

circulated in Latin

1436: Della Pittura circulated in Italian

Prologue, pp. 39-40:

open letter to painters working in

Book I (not assigned): on perspective

(painting as geometry)

Book II: the three parts of painting (pp. 63-85)

Book III: education of the artist (pp. 89-98)

III.

Of

Painting, Book II: The rhetoric of painting

Alberti divides painting into three parts or

stages:

1) line: drawing (Italian disegno)

2) composition: overall

organization of the painting, expressed by an underpainting

or blocking in of the drawing with dark colors. Composition is closely linked

to what Alberti calls istoria, the

narrative content of the painting. Composition refers to the overall structure

of the painting, including its spatial organization understood abstractly (use

of perspective, symmetrical or assymetrical

arrangement, etc.) Istoria refers to

the story told by the painting: its subject matter or theme. Both for Alberti

concern the overall unity of the work of art, and are not sharply distinguished

in his writing. If you want to distinguish them, think of “composition” as more

abstract, and “istoria” as involving content or meaning.

3) color: added last in Florentine painting, after

the drawing and the underpainting.

Ethos,

logos and pathos – the building blocks of rhetoric, translated into Renaissance

painting

Logos = istoria,

the narrative argument of the painting

Ethos = the dignity and appropriateness of

the human figures in the painting

Pathos = facial expressions, hand gestures,

and bodily poses and movements

A. Istoria

“I say composition is that rule in painting

by which the parts fit together in the painted work. The greatest work of the

painter is the istoria. Bodies are part

of the istoria, members are parts of the bodies, planes

are parts of the members.”

(p. 70; also, p. 72)

istoria:

> story, history, narrative, plot

> what the painting is about; its

content; the story it’s telling

> compare to logos

in rhetoric: the istoria is the

“argument” of the painting.

> “the greatest work of the painter”: a

plea for the painter as humanist, an intellectual whose work resembles that of a

poet, rhetorician, or historian

In a good istoria, all the details support the story:

“Bodies ought to harmonize together in the

istoria in both size and function. It would be

absurd for one who paints the Centaurs fighting after the banquet to leave a

vase of wine still standing.”

(p. 75)

Alberti observes (and recommends!) that Renaissance

paintings often include a commentator figure, who instructs the viwers how to react to the events depicted. The commentator

often exists at the threshold of the world of the picture and the world of the

viewers. The commentator figure is like a classical orator, who instructs his

listeners in the proper reaction to the events or arguments he recounts. In

addition to classical rhetoric, Renaissance painters would also have drawn on

the figure of the priest or preacher from church, and on masters of ceremony

from sacred theatre (mystery plays) and pageantry.

“In an istoria,

I like to see someone who admonishes and points out to us what is happening

there ...” (p. 78)

Visual

check: Find the commentator in this painting by Domenico

Ghirlandaio:

B. Ethos

“Again we ought to say that in composition

the members ought to have certain things in common. It would be absurd if the

hands of Helen or of Iphigenia were old and gnarled, or if Nestor’s breast were

youthful and his neck smooth... All the members ought to conform to a certain appropriateness...

In the composition of members we ought to follow what I have said about size,

function, kind and colour. Then everything has its dignity.” (p. 74)

According to

Alberti, human figures should be depicted in a manner appropriate to their age,

gender, social class, and function in the story. This emphasis on the

appropriateness of characters to their narrative situation parallels the

rhetorical idea of ethos or character. The orator should use his character to

lend further authority to his argument, and his argument should not exceed or

contradict his attributes as a speaker. “Dignity”

is another word for appropriateness in Alberti’s vocabulary. To be dignified,

according to Alberti, is to act in a manner appropriate to one’s age, sex, and

social role. With this definition in mind, in what sense are the following

drawings by Leonardo da Vinci “dignified” or

“appropriate” in Alberti’s sense?

C. Pathos

“The istoria

will move the soul of the beholder when each man painted there clearly shows

the movement of his own soul. It happens in nature that nothing more than

herself is found capable of things like herself; we weep with the weeping,

laugh with the laughing, and grieve with the grieving.” (p. 77)

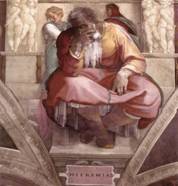

Alberti suggests that the painter depict

inner feeling or pathos through external expression, including facial

expressions, gesture, and bodily pose and movement. What emotions do you think

the following painting by Michelangelo is meant to express?

What are some of the ways in which the painter

Giotto represents grief in this painting?

In addition to classical rhetoric and oratory,

Renaissance painters also looked to

preaching (in church) and to theatre and dance for gestures that they could use

to represent emotion or pathos.