Plato_Lecture1

I.

Thinking, Making,

Doing

A preliminary Observation:

To think

(large use): To use concepts, to use conceptual terms in order to articulate –

verbally or mentally - a discourse that elucidates an issue, tries to find out

something, or solve a problem, through thinking. Paradigmatic figure: the

philosopher.

Traditional philosophical

thinking: very comprehensive, abstract and concerned with ‘deep’ issues like

‘the meaning and nature of life;’ ‘what kinds of things there are’ and whether

those kinds exhibit an order (ontology); how we ought to live (ethics), and –

of course: love in our text.

To make: The

action of bringing about a work by using material as means. Main features:

Either let a purpose or end be given; then find the means to realize it and set

yourself to work in order to realize it. (Paradigmatic figure: craftsman,

engineer) Or: to have an understanding according to which something can be

brought about. Then set out to bring it about, whether or not the result serves

a purpose. (Paradigmatic figure: the scientist)

To do: to

perform an action as realizing a value or a virtue. Cognitively: to know the

motives, reasons, consequences of one’s actions. Normatively: to evaluate and

control one’s actions. Paradigmatic figures: the statesman, the saint, life

lived as ‘examined life,’ the democrat (ideal!).

Are the three attitudes

alternatives? Most activities involve all three. All three need to combine for

something to be carried out in the best possible way. But the three elements

have different weights in different kinds of social activities. We criticize an

artist for merely being a good craftsman, or an engineer or scientist for not

caring for the uses made of his work, and a thinker for not considering

conditions under which his proposals can be realized, or of not being

dispassionate enough and thinking with an ideological bias or trying to justify

unquestioned interests.

The philosopher’s voice: “Thought by itself moves nothing, but

only thought directed at an end, and dealing with action. . . .

He who makes something always

has some further end in view: the act of making is not an end in itself, it is only means and belongs to something else. Whereas a thing done is

an end in itself.” (

Highly

problematic distinction and definition of concepts ‘thinking,’ ‘making,’

‘doing.’

II. My Project in this

Course:

Show two samples of

philosophical thinking, going back to its founding fathers. Philosophy aspires

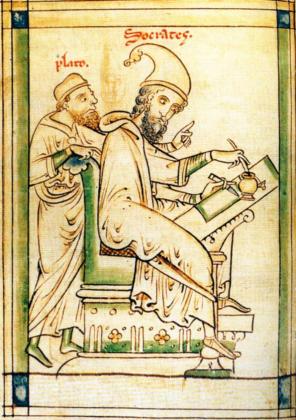

at being the representative of thinking in academia. Socrates – the one who did

not write – was Plato’s teacher; Plato was Aristotle’s teacher.

Two, or even three very different philosophical personae:

Socrates, the one of common origin who questions and argues. Plato,

the aristocrat who uses Socrates’ method to gain insight into eternal truths

and the good and orient his fellow citizens towards the right kind of life.

Aristotle, son of a doctor in the province, who wants to gain the most

comprehensive picture of nature, life, man and wants to guide us towards the

best possible realization of ourselves. Plato, the artistic

temperament. Aristotle, the scientific temperament.

III. The Symposium:

1. General:

“to

gather to drink together.” Plato makes it into a gathering for presentations

and discussions.

Choosing to

have “speeches in praise of ‘Eros’

lets the speeches be of the rhetorical genre of the encomium, i.e. of a speech meant to praise, normally a person. Does praise get in the way of truth? (fastforward to Agathon and Socrates’ questioning of

Agathon).

Philosophizing is here

performed in the form of drama: enacted on a scene, be it as exchange of

dialogue, be it as soliloquy of speech. The frame is not exploratory, but

laudatory. In addition, the participants compete for ‘best laudatory speech.’

Is that doing ‘thinking?’ Can one think ‘competitively?’ What is the

significance of presenting thinking in this form?

7 Speeches: Phaedrus,

Pausanias, Eryximachus, Aristophanes, Agathon, Diotima, Alcibiades. Opened,

interrupted, joined by dialogues: Apollodurus and friend .

The whole reported by Apollodurus who relates to his friend what he has been

told by a certain Aristodemus (173B.2), who was present but did not participate

in the debate. Both narrators pop up in the text from time to time to remind us

that we are reading something that is narrated, and to tell us anecdotal things

like Aristophanes’ hiccup. 1001 Nights!

Function of framing?

Speeches and dialogues

present very different ideas of love, or love in many different manifestations.

Are they ordered? Is there a thread? Sometimes the later ones offer

alternatives or supplements to the earlier one. Also some

criticism in the backward direction. Progress? Collection of internally unrelated attitudes towards love?

Obviously a

line of ascendance, at least towards Diotima’s speech. But, what does her speech do to the preceding ones?

How are the preceding speeches and exchanges related? What does it mean that

Alcibiades comes after her, telling his ‘platonic’ love story with Socrates,

and, in doing so, enacting it?

2. Speeches:

Phaedrus

presents love in the embellishing light of greatness, nobility, and as a device

that confers virtues. His picture of love is the idealized love in a society of

heroic values. An army made of lovers would be more courageous than other

armies (178E.4). Lovers are prepared to die for each other. Love guides lover

and beloved in giving them a sense of shame and pride. With those senses one

“acts well” (178D.2). His examples bare this out (Achilles, Alcestis). But also

the justification he offers to ground the greatness and dignity of ‘Eros’ He is the “first god designed” by

Earth. The most ancient is also the highest and most dignified.

Phaedrus, the beautiful young

man with whom Agathon is in love (and Socrates elsewhere), tells us what he

thinks one ought to say. He uses the scheme of the rhetorical genre ‘encomium.’

Also tries to be, as it were, ‘politically correct.’ Shows

that he has learned his lesson. But his picture is entirely normative,

and does not find much support in the facts. In addition, is the heroic ideal

really the best thing one can say about what or how love ought to be? Most of

the other speakers will carry the normative aspect elsewhere.

Phaedrus praise is therefore

partial, and partly off the mark. Write it off? He hits a truth. And he

articulates a possible manifestation of love.

Pausanias

exploits the weaknesses of Phaedrus’ speech. He also articulates a normative

ideal, some of it more what he would like it to be than what others

think. His strategy is to distinguish low and high love: Heavenly and Common

Aphrodite. The interesting core of his position is how he attributes aspects

and manifestations of love to the two sides.

Common Aphrodite

|

Heavenly Aphrodite

|

|

|

|

|

Of body |

Of soul |

|

Main object: intercourse,

physical intimacy |

Abstain from intimacy |

|

|

|

|

Each keeps his own and watches over his own |

Share everything |

|

Short-lived |

Stay together one’s whole

life |

|

|

|

|

For object: Yield quickly |

Resist, test the interest

of suitor |

|

To seduce or let oneself be

seduced by wealth or power |

To be motivated by genuine

affection |

|

Under conditions of ‘common

love’ it is shameful to be deceived |

If conditions of ‘heavenly

love’ are fulfilled, it is not shameful to be deceived |

Observations and problems:

Pausanias ideal is a relation

between an older man and an adolescent approaching adulthood that is not lived

as passion and physical intimacy, by someone who imposes restraint on himself

as concerns intimacy, preferably in

Women are not even considered

as lovers, only as objects of love. Law forbidding affairs

with young boys.

The most fascinating aspect

of Pausanias is the fact that he carves out a special normative ethics for his

preferred relation. Pausanias calls it “freedom.” Among the rules for what is

right and honorable in a homo-erotic relation:

Publicly declare your

interest is honorable.

Conquest (of what kind?) is

noble.

Attempt at conquest justifies

actions otherwise dishonorable such as servility and public self-humiliation

directed at the beloved.

Does love require and justify

a code of its own?

Pausanias is not very

explicit about what it is to give oneself to another man (183D.7). Would it not

mean that, for a noble man, it is right to engage in intimacy, but for someone

who is not noble that is not the case? I sense a self-licensing effort, hidden

behind the apparent ‘high’ moral stance.