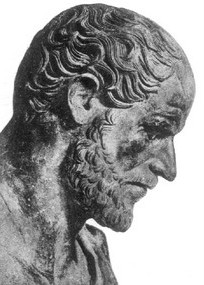

Aristotle (384-322 BCE).

Son of a doctor. Sent to

Groundbreaking work on pretty

much all aspects of the sciences, theory of science, psychology, ethics,

ontology, metaphysics and logic, rhetoric, literary theory. (The term

“metaphysics” is due to the name for Aristotle’s writings on fundamental

philosophical questions. Main traits of his philosophizing: Very abstract

philosophical discourse. Great systematizer; tries to organize everything he

finds into one huge order. Looks at the world as basically ordered by telos:

everything behaves or ought to behave in a purposeful way. (Modern thinking is

dominated by the idea of causal analysis). His ideas and his world-picture

dominated thought and science until the Renaissance, albeit in a Christianized

way. We will look at his ideas of soul (philosophical psychology) and how to

live a good life (ethics), and nature (Physics).

I.

Why be

interested in the soul?

“For what is a man profited,

if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? Or what shall a man

give in exchange for his soul.” (Matthew 16:27)

Me, caring for my soul; my

soul taking care of me. In this world. Aristotelian ethics is care for soul.

For another world?

The concept is value-laden.

Different sets of values lead to different models of the soul.

The Christian Idea of the Soul:

Soul that part in us we share with God. God’s spirit in us.

Given to us from God, immortal, returns to a trans-mundane existence after our

death (“Then shall the dust return to the

earth as it was: and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it”

(Ecclesiastes 12:7).

In

this world the soul is human will, understanding, and character, i.e. unique

personality. Feelings and desires belong to the flesh. Most importantly: the

Christian soul is free. Free to decide to do the good or to do evil, not

subjected to the senses in its decisions. Being the main agent and medium of

insight and control, it is through our souls that we conduct our lives, our

soul acting as a governing agency in us (

Each

human being has a unique soul, given to her or him in the process between

conception and birth (the Catholic church teaches that the soul is present from

the moment of conception). It is our most precious good, and calls for moral

protection of its being, as well as constant guidance.

From a transcendent point of

view the soul is the agency that is responsible for the life we lead before

God. Surviving our death, souls will be judged by God. If our life finds grace

before God, the soul will gain eternal life in Heaven and enjoy eternal

fellowship with God. If, on the other hand, the judgment is negative, the soul

will be punished for the sins of our lives. (An older theology: hell).

The Buddhist Soul:

[Adapted

from the article “Buddhism” in Encyclopedia Britannica.]

As

individuals we exist in separation and limitation, both of which ground desires

to overcome the obstacles, and desire is the basis of suffering.

Buddhism

rejects the idea that the soul exists as a metaphysical substance, but

recognizes the existence of the self as the subject of action in a practical and moral sense. Life

is a stream of becoming, a series of manifestations and extinctions, without an

underlying coherent agency. The concept of the individual ego is a delusion;

the objects with which people identify themselves—fortune, social position,

family, body, and even mind—are not their true selves. There is nothing permanent.

We can

overcome the delusion of the mundane self and attain no self (an atman). But that means that we deal with the appearance of

the self or soul. What we take to be our self consists of five aggregates or

constituents (khan has): (1) corporeality or physical forms, (2)

feelings or sensations, (3) ideations, (4) mental formations or dispositions,

and (5) consciousness. Human existence is only a composite of the five

aggregates, none of which is the self or soul. A person is in a process of

continuous change, and there is no fixed underlying entity.

Two

important elements of the complex and diverse Buddhist tradition: (1)We can

overcome the delusion of self by attaining states of non-selfness. Yoga

practices are a means towards this end. Not only can we exist in a state of

non-self. We are also more enlightened beings in that state, closer to our true

selves than when we move in the world of desire and identification with mundane

values. (2) On the other hand, depending on how we live, we are reborn in

different incarnations in other lives. This is of course difficult to conceive

without assumption about something permanent that ‘underlies’ different

existences.

Contrasting

the Christian and Buddhist Souls:

The two

religious attitudes – with their very different models of the soul, show quite

neatly how basic notions depend on basic values of world-views: the Christian

world-view modeling of the soul manifests the idea of a creator God to whom we

are responsible in our lives and beyond. It also lets itself be dominated by

the idea of a conflict in value between body and soul. The soul knows and

pursues the good, the body is dominated by desires and appetites that fall on

the bad side, and the idea that the soul ought to rule a recalcitrant and

basically immoral corporeal self.

The

Buddhist notion, on the other hand, conceives of our mundane existence in a

negative way. It is thus let to see a problem in what is commonly called

‘soul.’ In setting up a practice of overcoming the negative, the soul is put

into the role of that which is to be overcome, and the overcoming as the

shedding of an illusion.

Aristotle’s soul

The soul

is a well-circumscribed part of our whole being. First, everything that has

life also has soul. (413a20: “that which has soul is distinguished from that

which has not by life.”) Plants and animals have souls. As bodies are also

found in the world that is not alive, soul must be the distinctive feature of

life. But what are ‘body’ and ‘soul’ doing inside of the living unit, each of

them present in that unit, how are they united and what is each of them there?

The naïve

view: We turn to a living being. It is a substance in Aristotle’s terms: an

independent being distinct from other beings of its kind and of other kinds.

First we find a body, describable in biological term: the thing that lives. For

some of the living bodies we find we will say that this body is inhabited by a

soul that does what we ascribe to the psyche: it perceives, feels, remembers,

dreams, thinks, desires, wills. We will, perhaps, also ascribe structural

traits to that soul, things like character traits. These are NOT Aristotle’s

ideas.

The Hylomorphic

Model

Soul

as form, body as matter:

“Now the

soul is that by means of which, primarily, we live and perceive and think.

Hence it will be a kind of principle and form, and not matter or subject.” (414a13)

“The soul must be substance

qua form of a natural body which has life potentially” (412a19).

Body and

soul are, in relation to each other, matter and form of the living being. This

is Aristotle’s hylomorphic conception of man. Body is matter=hyle;

soul is form=morphe. The soul is the form of the body of a living being.

The body is the matter of a living being whose form is the soul.

What does

it mean to be form, or to be matter?

Start

with something that is a separate being of a certain kind. Aristotle calls it a

substance. A tree, a snake, a human being are substances, but also a house, a

knife or a lyra. Or start with something of another kind, because they can only

occur together with a separate being: a feeling or an emotion like anger, a

color like ‘red,’

Matter is

that, out of which that something is.

Form is

what we describe when we say what the something is.

Examples

for form: shape and size (spatial form) of as figure, duration, speed, rhythm

(temporal form), artifacts (house vis-à-vis brick and mortar), essential

features, genre, inner order and organization). Anger – a sophisticated case

(403a30): boiling of the blood as matter of anger, desire for retaliation as

form of anger.

Form of

process: continuous (, cyclical (of seasons); speed (of a moving object);

ripening (of the change in a fruit).

Forming

form: In general: the potential and tendency in things to assume a certain form

(of water molecules to arrange in the form snow crystals; constitution (of a

state); soul (of living beings).

Forms

confer whatness, but also bind together parts and elements: the form of the

sandstone rock binds together the grains of sand in the rock.

For the

head of Aristotle shown at the beginning: Its matter is the bronze out of which

it is made. Its form is ‘Aristotle’s head.’ (It shares that form with other

Aristotle heads.)

A first

comparison between living substances and substances that are not alive,

juxtaposing form and matter in each case:

|

soul :

body ~ Aristotle-head : bronze |

The analogy is from the point

of view of form and matter: Just as Aristotle-shape is form relative to bronze

as its matter in the statue, so soul is form relative to the body as its matter

in the living being. Relativity: bronze is matter in the sculpture, but it can

be form vis-à-vis molecules.

Form-matter

distinction for living beings:

The bust

is an artifact, we are not. Not yet, perhaps soon. We are interested in the

form and matter of living things. That means that we need to look for elements

that can count as form relative to the body. Now Aristotle’s decisive move: He

lets himself be guided by the idea that life is the shared essential

trait of all living beings, and that life is their shared form. ‘To be alive,’

‘to be a life’ is our most basic function, and also of the world of plants and

non-rational animals. (Note the process-indicating prefix “a-“ in “alive!).

Aristotle’s idea and thesis: The soul is, or better includes, the complex

system of life-constituting functions for the living being. Whatever

actively contributes to confer life to living beings possesses soul character.

Function as form. If all soul elements are absent, we do not have life. And all

and only those elements that contribute in a forming manner to the conduct of

life of a specific form of life count as soul- elements.

The

biological body cannot be a living body without a soul. According to Aristotle,

no live body is without soul. Attention: This is not the venerable animism that

attributes to each living being an individual complete soul, assuming that the

tree feels, perceives, acts intentionally, communicates with us, a soul that suffers when the

tree is hit and says ‘no’ when the wind gets into its crown and shakes it. This is the attitude of the fairy

tale (Lord of the Rings), of certain religions wrongly called primitive, and of

our own ancestors. Aristotle thinks differently. More precisely: he thinks the

issue, instead of basing his attitudes on faith.

How are body (matter) and soul (form) working together to

constitute a living being?

Highly

intransparent formulae: “The soul must be substance qua form of a natural body

which has life potentially.” (412a18) and “The soul will be the actuality of a

body of this kind,”i.e.of a “natural body which has life potentially.”

And “the soul is the first actuality of a natural body which has life

potentially.”

What

is Aristotle saying here? Taken in abstraction from all soul elements the body

of a living being is not alive. The body lacks the form necessary for ‘life.’

‘Actuality’ is both that there is action – the action of the form on/in the

body, and that there is something going on right now – to live is to be

enlivened. Two ingredients, then, in “the soul is actuality.

But,

in order to be able to be enlivened by a forming soul, that body must be apt to

receive that form, just as the bronze and the marble must be apt to

receive the form of the statue. This is why body, taken in isolation, has life

“only potentially.” The body brings to the enlivening form the matter – an

organization of flesh and blood, organs and body-parts. The “body has life

potentially.” Without that potential and that actualization to concur, we do

not have a living being. As a living being, the item with that form and that

matter is a substance. What is it that lets that substance be that particular

kind of living being, that goose, elephant or amoeba? We would use Linnaean

criteria for distinguishing them from each other and refer, ultimately, to

differences in body and bodily function. Aristotle thinks that it is the form,

and therefore the soul, that is ultimately responsible, because the soul has

formative power and function. So, the soul contributes the decisive element to

the living substance: “the soul is substance qua form:” meaning: What kind of

substance that being is the item’s soul-function. The body only lends its

potentiality to the compound. (The conception lends itself to the idea that

there could be an elephant’s soul in a mouse, or woman’s soul in a man’s body.)

(Note

the prefix “en-“ in “ensouling” and “enlivening.” It presents the following

verb as saying that there is an activity that brings about a result.) These

formative activities are of the kind of a process and an activity; they are

‘actuality.’ The soul is therefore the actuality of a living body. ‘Actuality’

says two things: on the one hand, the soul is a condition for life; on the

other hand, being alive is an activity first, and a state only second. The

form-matter distinction is thus a first factor that lets the Aristotelian soul

be distinct from what mind-functions are for us. For Aristotle, life=Bios

is soul-activity!

What,

then, is the body taken in isolation – and what does the soul do to the body

when it enlivens its body? The body in isolation, considered without the soul,

is close to the item that lies before us right after death, or better, in

cardiac arrest: all the organs are there, everything that allows life-processes

to unfold is in place. But the processes do not take place. These

processes may resume, and if they do, the Aristotelian life-conferring soul

returns to its matter and actualizes it. (Play this through for different

stages of human gestation from conception to birth. Is there a likely stage or

development for the life-conferring soul to be in place? Where would that

be?).

Can body and soul/mind exist separately?

The

fact that soul is enlivening form to the potentially living body has an

immediate consequence. Christian theology has answered he question right from

the start in Genesis 2:7: “And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the

ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a

living soul.” But philosophy has been plagued by the question whether body and

soul can exist independently from each other. You have heard that the Christian

religious idea asserts independence of the two. And you will hear soon from Ann

that Descartes thinks so too. The idea of separate existence or ontological

difference of mind and body is dualism of body and mind, body and soul. Its

opponents claim that body and mind do not have independent existence, and often

achieve this by claiming that there is only one kind of item: either everything

is material – both body and mind, or everything is mind, bodies and matter as

well as soul. These are two monist positions: Materialism of the soul, idealism

or animism of the world.

Aristotle

sends them back to back, taking a position that is neither dualist monist.: “It is not necessary to ask whether soul and body are

one, just as it is not necessary to ask whether the wax and its shape are one,

nor generally whether the matter of each thing and that of which it is the

matter are one. For even if one and being are spoken of in several ways, what

is properly so spoken of is the actuality” (412b6-9).

No

after-life for the soul after loss of the body it enlivens. I do not think

Aristotle believes in an after-life in Hades, in form of bodiless shadow. All

that can be said about the soul after death is that it is a potentiality for

ensouling. And, as the uniqueness of the individual substance and the

remembered trajectory of a life contribute decisively to the individuality of

the soul in a living being, that individuality depends on the body. In other

words: No continuation of individual soul, not even in the form of a lifeless

shadow (Greek mythology), a soul that can be reincarnated (Buddhism) or a soul

that can be subject to punishment or bliss in an after-life (Christianity).

Body

and soul are two, because they play different roles in a living being. But they

are not themselves substances, precisely because they cannot exist independently.

They are not parts of the living being either, for they do not function as

components. They are codependent: the body without the soul is a being that has

lost its life and has lost the capacity for self-maintenance, also as a body.

The soul that vanishes from the body is deprived from the matter that gives

existence to it as a living soul. It is not the body that walks and the soul

that feels. Both are activities of the whole being, in our case of the person.

The person walks and feels. And walking and feeling both involve soul and body,

in different roles.

Similar

for the body: without the soul it is not alive. It is potential for life as

long as the body is a ready recipient for the enlivening form, or is

‘ensoulable.’ The body does therefore not have special dignity after death.

Soul-body

interactions.

Interactions:

Behavior occurring between two agents or agencies in such a way that the action

of one directed at the other is connected with the action of the other at the

direction of the first: action1 (x à y) connected with action2

(y à x)

The

basic form of interaction has already been discussed: the soul confers life to

the body, which, in isolation is alive only potentially. The body in turn

offers the potential for actualization of the whole being to the soul, which

does not have reality without being embodied. The two are interdependent. When

one occurs, the other also occurs. But we still have, as it were, two agencies,

and therefore the possibility to analyze a phenomenon from the perspective of

the body or of the soul. Anger, once again (403a30): anger – an emotion – is also boiling of the blood. But it is

also desire for retaliation, and desire is a soul function.

The

soul expressed in the body:

Nothing

obliges Aristotle to think of the soul as an element that is ontologically

spiritual, different from elements that are ontologically material. The

distinction between form and matter is at any rate a relative and functional

distinction: Forming soul is whatever is the form constituting element

vis-à-vis something that is the formed – matter – in this connection.

His

thinking is different from ours, tinted by 2000 years of Platonism and

Christianity. But he thinks of an interaction here, between two agencies that

play different roles in that interaction, whether they look to us as physical

or as mental. We do not think like that. How can one think like Aristotle?

First, he does not possess the chemical knowledge we have. Philosophically more

interesting is the question: How can he even distinguish forming activity from

formed form? If, as he says, the body is prepared to receive the form of life –

the body is life potentially – how can one even distinguish the forming force

and the formed recipient? Our chemical analysis does not do this. Indeed, it

does not even have a model that calls for that thought. Our genetic perspective

does exactly that, but only for growth and renewal of cells. Alas, also for the

degeneration of aging. It looks as if we could think only in terms that

distinguish soul and body as ontologically different, mental here and corporeal

there, conceiving of the forming soul as if it were a sculptor who works on his

material. Nature as clay animation!?

NOT

Aristotle’s conception. To be form and formative does not imply being mental in

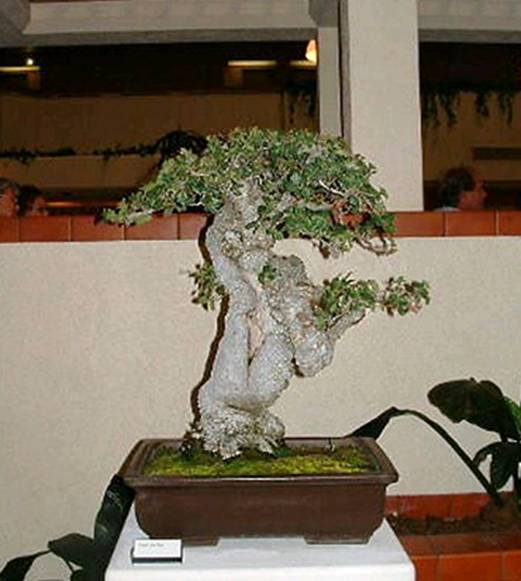

the sense of ‘mind-stuff.’ The Bonsai tree shows in its appearance what its

soul works from the inside:

[From:

Finding a

Soul in Bonsai. http://www.artofbonsai.org/forum/viewtopic.php?t=961

Part

of the caption: “The Japanese have a word known as Kami. As far as I know I am

about the only person who has chosen to associate this word with Bonsai. Other

Bonsaists choose to use Wabi and Sabi when defining the

quasi-spiritual aspects of bonsai. Kami is for lack of a better definition

defined as spirit or soul, an almost personality that inhabits things of great

beauty, power, and artistry. It is a force that almost gives a thing a life of

its own that supersedes a tree or a pot or a sword, or a landscape.”

The

distinction between an active, forming function in our plant and a passive,

formed function makes sense if we make one important assumption: the body that

is enlivened by the nutritive and self-maintaining soul of the plant is not

just lying there, waiting to be ensouled, perhaps longing for it like

Snow-White for the kiss of her Prince. The body is also recalcitrant. It has

its own resistance to being kept alive and brought into its form. The form has

to constantly overcome that resistance in maintaining that body alive and

giving to it its typical form. Taken separately, the body is not just

propensity to be ensouled, made and kept alive. It is also an item in its own

right – potentially – and that resistance needs constantly to be overcome. We

see it at work in illnesses, aging, in the deviations that can occur in

generation. The idea of soul as enlivening form and body as formed life is

therefore an idea that combines the idea of fit – the propensity of each to

unite with the other to constitute a specific form of life and the idea

that there is an opposing tendency in life – something that opposes being in

that form. Only together do they account for life: Not ‘nature as clay

animation,’ but: nature as antagonism of forces. Nature is the world of change.

Its living domain changes as a consequence of internal antagonism.

A

comparison of soul features

|

- - - - - - - - - - -

Aristotle - - - - - - - - - - - |

- - - - - - - - - - -

Modern - - - - - - - - - - - |

|

|

|

|

Hylomorphism: body and soul

functionally distinct but in interdependent relation. Neither dualism (Descartes)

nor monism (materialisms) |

Dualisms: body and soul

each have their own being; may have

independent destinies. Monisms: materialism denies

independent being to soul/mind; a certain brand of idealism says everything

is soul. |

|

|

|

|

Soul enlivens body; body

gives reality and sustains soul in existence (gives ‘actuality’ to soul).

Soul in principle not linked to mind, as we understand it. |

Biological life is mind-independent,

therefore not ensouled. Mind-functions are

‘add-ons’ to life. |

|

|

|

|

Hierarchy of basic

faculties: |

Multitude and plurality of

functions; related, but without systematic order, only partially ordered. |

|

|

|

|

Soul-functions are active,

enabling sources of performances, corporeal functions are soul-activated; affective

and perceptive soul-functions show double aspect: soul appearance and

corporeal appearance. Example: sight is due to

the eye-soul making the eye perform its purpose, but depends on the eye being

hit by object, and recording the object. Hylomorphist: sight is

interaction of eye-matter and sight-form. |

Mind-functions are

dependent on body-functions; Example: sight either

coincides with or is due to neurological processes in the eye, the nerves and

the brain. Reductionist: sight is but

a complex of neurological events. |