A Midsummer Night’s

Dream

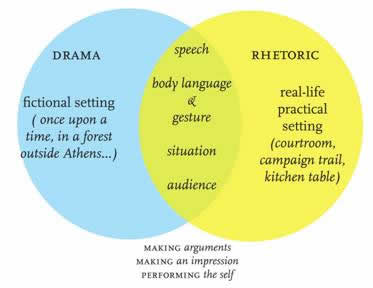

Lecture Two: Drama

and Rhetoric

drama:

composed of actors speaking lines, using intonation, body, and gesture to

communicate meaning and emotion in a specific narrative situation, to an on-stage

and an offstage audience.

rhetoric:

from the Greek word for “speech” or “spoken,” rhetoric is the art of

persuasion. Like theatre, rhetoric uses the speaking body to achieve a

particular end (winning a court case, reaching a decision, or praising a

beloved) in relation to an audience.

Drama and rhetoric as

forms of making: Making arguments Making an impression Performing the self Rhetorical example #1:

Egeus makes his case Egeus pleads his case

before Theseus, Duke of Athens, I.i: Full of vexation

come I, with complaint Against my child, my

daughter Hermia. Stand forth,

Demetrius. My noble lord, This man hath my

consent to marry her. Stand forth,

Lysander: and my gracious duke, This man hath

bewitch’d the bosom of my child; Thou, thou, Lysander,

thou hast given her rhymes, And interchanged

love-tokens with my child: Thou hast by

moonlight at her window sung, With feigning voice

verses of feigning love, And stolen the

impression of her fantasy With bracelets of

thy hair, rings, gawds, conceits, Knacks, trifles,

nosegays, sweetmeats, messengers Of strong

prevailment in unharden’d youth: With cunning hast

thou filch’d my daughter’s heart, Turn’d her

obedience, which is due to me, To stubborn

harshness. And, my gracious Duke, Be it so she will

not here before your grace Consent to marry

with Demetrius, I beg the ancient

privilege of As she is mine, I

may dispose of her, Which shall be

either to this gentleman Or to her death,

according to our law Immediately provided

in that case. (Act One, Scene One, lines 22-45; p. 4-5) complaint:

Egeus bringing a formal grievance against his daughter and Lysander in a court

of law. logos [argument]:

Egeus accuses Lysander of witchcraft and seduction. ethos [character and authority of the

speaker]: Egeus speaks with the authority of

a father, supported by the laws of pathos [emotion]:

Egeus aims to inspire sympathy and respect for the rightness of his cause. He

also may want to rouse fear of generalized disobedience and decay of order that

will result if Hermia is allowed to choose her own husband. audience:

Egeus addresses Theseus as the ruler of Rhetorical Example #2:

Lysander’s Defense I am, my lord, as

well derived as he, As well possess’d;

my love is more than his; My fortunes every

way as fairly rank’d, If not with vantage,

as Demetrius’; And, which is more

than all these boasts can be, I am beloved of

beauteous Hermia: Why should not I

then prosecute my right? Demetrius, I’ll

avouch it to his head, Made love to Nedar’s

daughter, Helena, And won her soul;

and she, sweet lady, dotes, Devoutly dotes,

dotes in idolatry, Upon this spotted

and inconstant man. (Act One, Scene One, lines 99-110; p. 6-7) prosecute my right:

Lysander makes his counter-argument. logos [argument]:

Lysander argues that he is of the same social class as Demetrius, and besides,

Hermia loves him! Moreover, Demetrius used to love ethos [character and authority of the

speaker]: Lysander speaks as a good-looking

young man from a high social class. He also impugns the ethos or character of

Demetrius. pathos [emotion]:

Lysander tries to build sympathy for himself and Hermia, but also for audience:

Lysander addresses Theseus as the ruler of Rhetorical Example #3:

Titania’s custody argument TITANIA Set your heart at rest: (II.i.122-127; pp. 21-22) logos or argument:

The Indian Boy belongs in her care because of Titania’s friendship with his

dead mother. ethos [character and authority of the speaker]: Titania speaks as a mature woman,

with knowledge of birth and death. Her authority is based on the strength of

her relationships, not just her status or experience. pathos or emotion:

Titania builds her case out of her own sense of mourning and loss. She draws sympathy

for her position by showing her feelings for another person.

use of metaphors (part of logos):

1. Ships with sails

filled with wind look like pregnant women. 2. The pregnant woman,

fetching treats for Titania, resembles a ship filled with merchandise. Paper 4: a rhetorical

analysis of a dramatic scene logos: What is the argument of the passage, and how does the speaker make the

argument? ethos: What kind

of character does the speaker project in making the argument? (and how does the

speaker represent the character of others on stage in order to achieve his or

her persuasive ends?) pathos: What

emotions is the speaker trying to arouse in his on-stage audience, and by what

means? how do we respond to these ploys as the audience off-stage? situation: Who is

being addressed? for what purpose? staging: How might an actor use gesture, tone, body language, or props

to heighten the rhetorical impact of the speech? What about lighting, stage

sets, or other resources of theatrical making? III.

Into the Woods: The Young Lovers Get Lost Recall the situation at the beginning of the play: >Hermia and Lysander are in love >Demetrius used to love > FOUR

LOVERS ON STAGE AGAIN: Act Three,

Scene Two HERMIA: O me! you juggler! you canker-blossom! You thief

of love! what, have you come by night And stolen

my love’s heart from him? Have you

no modesty, no maiden shame, No touch

of bashfulness? What, will you tear Impatient

answers from my gentle tongue? Fie, fie! you counterfeit, you puppet, you! HERMIA: Puppet? why so? ay, that

way goes the game. Now I

perceive that she hath made compare Between

our statures; she hath urged her height; And with

her personage, her tall personage, Her

height, forsooth, she hath prevail’d with him. And are

you grown so high in his esteem; Because I

am so dwarfish and so low? How low am

I, thou painted maypole? speak; How low am

I? I am not yet so low But that my nails can reach unto

thine eyes. Juggler: street performer;

someone who uses sleight of hand to switch things around in the air Counterfeit: liar,

faker, pretend friend Puppet: doll, puppet.

Toy, theatrical prop. Made thing. Thou painted maypole:

maying imagery comes back – in the form

of insults! > Are they all simply “puppets” and “balls in the air,” or

are they also authors of their own stories, acting out of a prehistory of

friendship and fliration? evidence for past

relationships: Lysander

to Hermia: “In the wood, a league without the town, Where I did meet thee once with To do observance to a morn of May, There will I stay for thee.” (I.i.165-68;

p. 9) >

They have met in the forest before, as a group. > Then

as now, “maying” provided a social script for their mixing and mingling. into the woods: making, unmaking, and remaking

relationships In the play, the fairies are “real.”

Puck and Oberon do act upon the lovers. Yet Shakespeare also gives us enough

sense of a history of friendship and flirtation among the young people to give

the switches some psychological coherence. Do you enjoy Shakespearean Insults? Visit The Generator: http://www.pangloss.com/seidel/Shaker/index.html?

The fairy land buys not the child of me.

His mother was a votaress of my order:

And, in the spiced Indian air, by night,

Full often hath she gossip'd by my side,

And sat with me on Neptune's yellow sands,

Marking the embarked traders on the flood,

When we have laugh'd to see the sails conceive

And grow big-bellied with the wanton wind;

Which she, with pretty and with swimming gait

Following,--her womb then rich with my young squire,--

Would imitate, and sail upon the land,

To fetch me trifles, and return again,

As from a voyage, rich with merchandise.

But she, being mortal, of that boy did die;

And for her sake do I rear up her boy,

And for her sake I will not part with him.

AUDIENCE: Titania is speaking to her husband, who is also king of the fairies. In the prior speech on climate change, she speaks to their joint responsibility for disturbances in the natural order.