Mahalia Knight

Prospectus

On February 17, 1913 the

International Exhibition of American and European art opened at the 69th

Regiment Armory in New York; approximately some 1,300 modern works of Art both

American and European origin were shown, establishing the show as the most

prominent if not largest American exhibition by that time. The importance of the show, however, rests

not necessarily in the project’s scale but the pieces that were put on display. Although a modern tradition

of art theory and work had begun to be established, exemplified by the “Ashcan

School” or “The Eight”, even the most conservative estimates place American art

sensibilities at least twenty years behind European modern art.

The art show had been

put on with the pure intention of introducing Americans to the discoveries and

trends taking place in modern European art.

Although contemporary art movements, such as the loosely associated

“Ashcan” school of artists or infamous group of “Eight” had, in their

investigation of non-classical subjects via a photorealistic sensibility, begun

to experiment on the fridge of modern art, even the most modern of American

artistic rhetoric did not attempt the level of abstraction or intellectualism

associated with European modern art. An

article printed by the Daily Chicago

Tribune, posing the question “When is art art? When wicked?” in response to the recent

impoundment of reproduction of Chabas’ “September

Morn” from a Chicago store window under the pretext of the work’s lack of

“good morals” only further influenced the Association of American Artists and

Painters to hold an education exhibition in order to higher the American

standard of acceptable art.

The International

Exhibition, which would ultimately become to be known as the Armory Show, was

an artistic feat in itself; approximately some 1,300 works of art, both

painting and sculpture, were put on exhibition, of both American and European

origins. However, although the show

inspired a new dialogue on the state of modern art in

The presence of advanced

modern that art so conflicted with pre-existing American sensibilities inspired

different forms of action manifested in the forms of protest. A

On the final day of the

Armory Show’s stay at the Chicago Institute, a crowd of art students gathered

out on the steps of the museum in order to hold a protest against the art of

the show; costumed and arranged in a “funeral procession”, the students

proceeded to burn prints of Matisse’s work.

Similar lampoons against the Armory Show had already been staged,

including the printing of caricatures of the works in newspapers and

competitions held between Academic artists in order to produce the next, best

“modern” work of art (all of the subsequent entries would later be revealed as too conservative, as only the “maddest”

of men could successfully paint “genuine” “cubis[m]”). “Futurism” had even already been already

reported as “dead” by the Architectural League a month prior.

What is unique of the

congregation of the students outside the Art Institute is the extent the

students took to resist the art they had confronted them. As opposed to the majority of conversations

and debates that been inspired by the show, the students chose to actively

bring their issues to the physical location of the art in question, rather than

passively criticizing the show from afar or engaging in the popular printed

forum. Furthermore, the students chose

to burn both the prints and effigy of Matisse; a destructive act that

symbolized the highest level of contempt the students could possibly hold for

the art on display. What I am most

interested in is the mock “trial” the held, in which Matisse was both accused

“guilty” and sentenced to “death”.

I argue that the student’s protest and

subsequent “trial” can act as a microcosm of the overall state of relations

between the public and the art of the show.

The public, like the art students, were confused and dismayed by the

European advancements in art and, in their collective confusion as to how to

react against art that contradicted Academic values of art, staged similar

motley demonstrations against the art.

Just as the students placed Matisse on trial and convicted him without a

proper defense, so too did the American public place Modern Art on trial and

sentence it to mediocrity without listening to the counterargument.

I argue that the student’s protest and

subsequent “trial” can act as a microcosm of the overall state of relations

between the public and the art of the show.

The public, like the art students, were confused and dismayed by the

European advancements in art and, in their collective confusion as to how to

react against art that contradicted Academic values of art, staged similar

motley demonstrations against the art.

Just as the students placed Matisse on trial and convicted him without a

proper defense, so too did the American public place Modern Art on trial and

sentence it to mediocrity without listening to the counterargument.

I find it interesting

that it would be art students who would lead the most voracious protest against

the art of the Armory Show; I wish to explore and discuss what it was about the

art that offended so, in hopes of understanding the source of the public

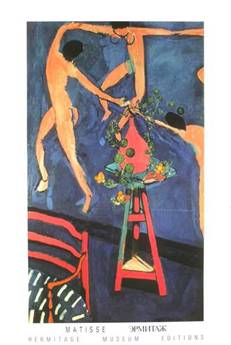

apprehension. I intend to conduct a

close study of Matisse’s Les Capucines

(La Danse II) and discuss what of the European sensibility that celebrated

the “spark of life” so perturbed the public and would motivate the art students

to call for its death.

I hope to discuss public

interaction with art and explore what it means to reject art and it subsequent implications. Primarily, I will be reading and making sense

of newspaper articles, letters, pamphlets, and art contemporary to the show in

order to best understand its nature. I

also am interested in the, sometimes conflicting, historical arguments written

on the Armory Show, also attempting to deduce the essence and impact of the

show. Therefore, my intensions of this

research paper are not to settle the final debate of how important the Armory

Show was or even its necessary place in art history. Does public acceptance of art redeem and

secure its value? If the nature of

public forum is not favorable, would the art exhibition be considered one of

non-success? Is there a correct place of

art within the social context?

.